The Destruction Of The Kakhovka Dam May Have Made It Impossible To Restart ZNPP For A Longer Period

Prof. Dr. Attila Aszódi

As extensively covered by international news reports, the Kakhovka dam on the Dnieper River, located some 120 km south-west downstream from the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP), exploded at dawn on 6 June 2023 during the Russian-Ukrainian war. The dam failure resulted in significant flooding downstream of the dam and a drastic drop in water levels at the power plant.

At the time of the dam explosion, 5 of the 6 units of the ZNPP were in cold shutdown, while 1 unit (No. 5) was supplying steam to the site in a so-called hot shutdown state. Since then (on 8 June), the IAEA reported that the Ukrainian nuclear safety authority had given the order to put the last unit in cold shutdown. This is a reasonable step in the circumstances, as the possibilities of providing cooling water have been significantly reduced by the explosion of the dam. The level of safety at the site has therefore been reduced and the operators can unfortunately also expect an intensification of hostilities in the area.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency and other reports, the level of the Kahovka reservoir at the power plant dropped at a rate of about 10 cm/hour in the hours after the dam was detonated, later decreasing to about 4-5 cm/hour. At the time of the dam explosion, the water level in the reservoir was 17 m. Energoatom, the Ukrainian energy company that owns ZNPP, said on its website that at 8:00 am on Friday 9 June 2023, the level of the Kakhovka reservoir at the power plant was 11.74 m (5 m lower than the initial level), but it then continued to fall.

Source: t.me/energoatom_ua

At the time of writing, on Sunday evening 11 June 2023, the Energoatom Telegram channel reports that at 6:00 this morning the water level was 9.45 m, about 7.5 m lower than the initial water level.

Source: t.me/energoatom_ua

This value is significantly lower than what the plant’s cooling system was designed for. The chief executive of Energoatom had previously stated that below 13.3 m it was not possible to ensure that the plant’s cooling water pumps could draw water from the Kakhovka reservoir. According to the German GRS website, normal operational access to the reservoir water is not guaranteed below 12.7 metres. The IAEA is currently investigating why there is a discrepancy between the water level values indicated in the various reports.

What is certain is that the current water level of less than 10 metres is well below the critical level. This means, therefore, that at the current spring flow of the Dnieper, such a low water level would be reached without the Kakhovka dam, which would not provide sufficient water level for the plant’s built-in cooling water pumps. The drop in the Dnieper’s level is believed to have moved the waterfront hundreds of metres away from the pumping station. At the current water level, direct access to the Dnieper is likely to be possible only with the help of temporary mobile pumps and flexible fire hoses.

As I wrote in my short report of 6 June (available in Hungarian), there is a cooling pond with a volume of 47 million m3 next to the power plant, which is – partially – independent of the Kakhovka reservoir of the Dnieper. In this cooling pond, the water level can be maintained even in the current situation, as shown in the figure above, where the water level was 16.67 m on Sunday morning, thus ensuring a longer supply of cooling water.

In addition to the large cooling water basin, each unit has also spray ponds to cool the essential cooling water systems. These spray ponds can even be refilled from a drinking water well to provide the necessary cooling function in the shutdown state. But these can only provide the cooling function required in the shutdown state, they do not have sufficient capacity for normal power operation! Unfortunately, the wall of the 47 million m3 cooling water basin can be destroyed by a single artillery hit, so it cannot be considered a stable source of cooling water in the present situation.

The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant on the left bank of the Dnieper River (Ph: Google Maps)

In this situation, it will be very difficult to decide whether to restart the units. As without the Kakhovka dam the above-mentioned water level has developed in the Kakhovka reservoir of the Dnieper, in my opinion it will be very difficult to ensure normal operation of the Zaporizhzhia NPP. Thus, it is even conceivable that the NPP will not be restarted until the Kakhovka dam is rebuilt (or otherwise a stable high water level in the river section of the plant is ensured).

This could hardly have been the intention of either the Russian or the Ukrainian side. I think that the Ukrainian party wanted their power station back as soon as possible, and the Russian party could have been preparing to supply electricity to Crimea and the newly occupied territories from here. With the inability of normal operational cooling, restarting will be quite difficult and it could take years before any of the units at the Zaporizhzhia NPP are operational again.

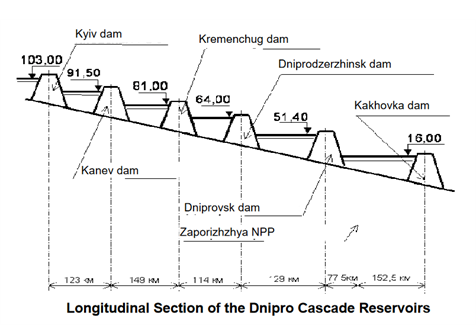

Let me note here that there are 5 more dams on the Dnieper River above the ZNPP, which unfortunately could be another target in the war. The only reassurance from a nuclear safety point of view is that the ZNPP’s ground level is 22 metres, while the Ukrainian side’s post-Fukushima stress test report states that the maximum possible water level in the Kakhovka reservoir is 19.36 metres, so that, according to the Ukrainian side, even if the water structures upstream of the plant were damaged, the nuclear power plant would not be flooded. The plant is therefore protected from a flooding-type external initiating event.

Diagram of the Ukrainian national report on the Dnieper dam system for the European stress test after the Fukushima accident.

My final comment is that the loss of the Kakhovka dam is also problematic for ZNPP in the sense that the hydroelectric power plant at the Kakhovka dam was one of the emergency power sources for the nuclear power plant. Of course, it still has a number of transmission line connections (when they are not being bombed), but the Kakhovka hydro plant was one of the nearby plants from which the nuclear plant could get external power in case of need.

Prof. Dr. Attila Aszódi

Full professor at the Institute of Nuclear Techniques of Budapest University of Technology and Economics. Currently, he is the dean of the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (Hungary). He took part in several projects of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the European Commission. He has more than 300 published scientific articles. His research interest is reactor safety, thermal hydraulics of nuclear reactors, Computational Fluid Dynamics, Particle Image Velocimetry, nuclear power plants, energy policy and sustainability.